Scrapbook #2 (The Fourth Of July, 2023)

An Irregular Series Wherein I Take My Personal Interests Personally

Every so often, I post a list of film-related things that have a hold on my thinking, experience, and interest. I imagine it as a way for readers to get to know me a little bit better (if you’d like), or perhaps as a different perspective on film culture. Please feel free to share your interests and thoughts in the comments— I cherish the conversation.

Reject All American: Robert Altman’s “Nashville”

Robert Altman’s “Nashville” is my favorite of his films, but was one I had never seen in a theater. So, when I saw it was playing at my local cinema on the Saturday morning I was supposed to leave for the 4th of July holiday weekend, I decided to do my patriotic duty and promptly changed my travel plans by a few hours to go and see it on the big screen at last. I’m so glad I did1.

“Nashville” remains a scathing look at the maudlin narcissism of American self-regard, the monied interests that feed it and upon it, and the deep vein of violence and exploitation from which it draws its power. It is also a brilliantly funny satire, with the film’s own outsider perspective sitting squarely within the bullseye of its withering gaze— Hollywood stars dip in and out, Californians and counterculture denizens stick out like sore thumbs against the conservative backdrop of honky tonks, dive bars, and working class cultural institutions. But today, it is the film’s political critique that feels more timely than ever.

Watching “Nashville” again, it struck me that all of the film’s narrative mechanisms are spokes in a wheel driven by a fictional third-party candidate for President named Hal Phillip Walker. It is Walker’s disembodied voice that opens the film, blaring from the rooftop speakers of his campaign van, decrying the state of American politics, and demanding the end of its two-party system in the name of his own campaign’s new Replacement Party. Altman uses Walker’s platform not only as a form of satirical populism, but as an actual critique of political imagination in the wake of the lost dream of the 1960s (symbolized by the assassinations of the Kennedy brothers) and the collapse of public faith in politics in post-Watergate America. Let’s replace it all… with more bullshit2.

It is not a coincidence that Walker’s campaign is led on the ground by the cynical Californian John Triplette (played with sneering duplicity by the great Michael Murphy) who manipulates the city’s political machine via his local proxy Delbert Reese (a typically brilliant Ned Beatty) to co-opt the stars of country music into Walker’s service. What Triplette understands is that Nashville itself— “The Athens Of The South3”— is the perfect place for Walker’s message, a city built upon traditional country music, the rural populist’s soundtrack for the American Dream, and with its own social and artistic hierarchies, engaged in the competitive push-pull of celebrity and down-home connection, those “American roots” that Walker’s campaign hopes to re-establish.

Using this framework to explore white America, Altman and his camera remain alive to all of the opportunity presented by this premise, refusing a fixed point of view for perhaps his best piece of ensemble-driven storytelling, creating a mosaic of a community whose belief in its own values continues to blind it to the currents of pain just below the surface. There’s the racism4 experienced by singer Tommy Brown5 (Timothy Brown), whose career places him outside the norms of both the country music community and Nashville’s black community. Then there’s the internalized misogyny of the battle between Connie White6 (Karen Black) and Nashville’s queen of the scene Barbara Jean7 (Ronne Blakley), a superstar who seems perpetually on the verge of losing it despite the best efforts of the legendary star Haven Hamilton8 (Henry Gibson) to keep her spotlight burning so that he might continue to join her in it.

The impact of these forces, personal and political, are twinned in the characters of Glenn Kelly (Scott Glenn), a Vietnam veteran whose obsession with Barbara Jean was inspired by his mother’s love of her music, and Kenny Fraiser (David Hayward), whose own overbearing mother seems to have driven him away from home and toward the fringes of Nashville’s music scene. Unlike the stars and strivers that surround them, Glenn and Kenny represent the current of violence that moves beneath all of American politics— war (Glenn) and the twisted social and emotional damage that drives stochastic violence (Kenny). Glenn and Kenny are not only twinned in presentation (as white male outsiders), but in shot after shot, often near or directly next to one another— as the film moves toward its conclusion, you understand that Glenn is Altman’s countercultural feint, the damaged veteran soldier whose presumptive capacity for violence underscores his stalker-like presence around Barbara Jean and her entourage.

But when the film’s actual conclusion inevitably arrives like the tragic 1970s B-side to Altamont’s demolition of the dream of the 1960s, there is no doubt at all about what the film is showing us: a culture that refuses to honestly confront the real meaning of its own politics will continue to reap what it has sown. Hal Phillip Walker’s Replacement Party populism foreshadows so much of what has made American politics so ugly— a sense of powerlessness, envy, entitlement, and social disconnection fostering a society fueled by the lie of its own self-certainty and victimization. And when that cynical, exploitative politics unites with a deeply sentimental, narcissistic culture? “Nashville” is Altman looking Hollywood and history squarely in the eye and refusing to sing along.

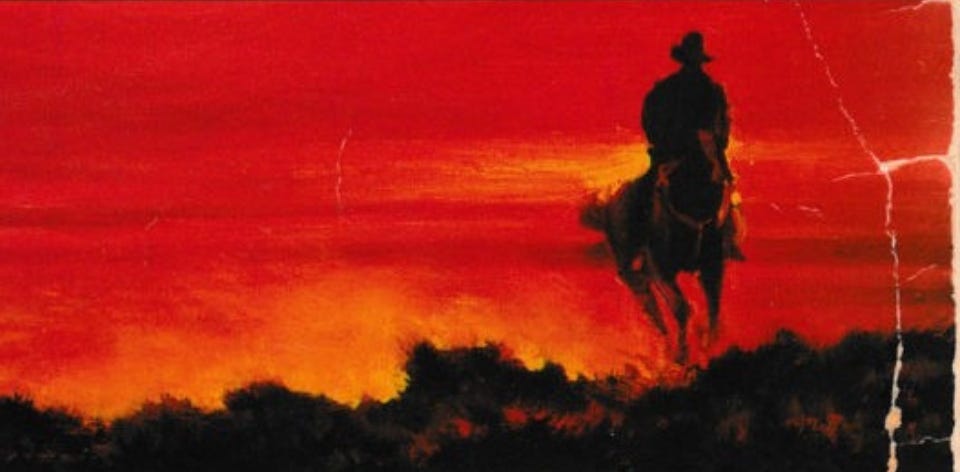

Reading Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy

Smoke from distant wildfires drifted down from the North, past the dry mountain escarpments and across the sun itself in order to settle over him, hanging like the charred remains of unlucky men who swung by their heels from unholy gallows. He picked up the book and moved across the wooden floor to the chair wedged into the corner of the room, put his weight down into it, and sunk like torn feet into the sediment of an angry river bed, surrounded by rising clouds of words that no man in his usual mind would pick out in conversation. His fingertips grazed at the edges of the pages, soft and dull, anticipating their movement into the past, black ink pressed into them like small ribbons of nightfall. He read on.

His eyes passed sentences by —slow, careful, dragged on by the momentum of the words themselves toward whatever fresh horror awaited. Trust was something that no reader could countenance. Every new character raised only the question of his own death. Solace was fleeting, atrocity inevitable, the fate of every living thing that would make its way across the parched land and onto the page. He read on.

The words presented America, her inherent need for blood without known capacity, gore dripping from paragraphs, the entrails of history cooked by the heat, blackened into wicked sentences. Death pulls her empire forward like a team of broken oxen, breathing in the romance of lawlessness and exhaling the barbarous absence of law. Justice is a trick played by devils made of flesh, the idea of which proved nothing more than a costly hesitation. His desire for it only confounded his attempts to put the words aside or escape their hard truths. This was not the place for it.

The truth is, there is no company that holds against the world, just a man himself, taking or taken, instantly gone or passed by, and either way unremembered in the cold light of the morning’s frost. The novel was a dirty mirror, held up to see, and there was everything to be took from its broken image. This was the actual state of things, a history rotting beneath a shining hope that was, itself, just another hopelessness. He read on until the book thinned itself out, the last pages extinguishing their last life, and the devil dancing clean through to the end.

Then, nothing more to see, he closed the book and was of a mind to let himself wander a bit, adrift in his own time, ankle deep in the rivers of violence against which it was built, thinking of the rough feel of the rope that continued to hold time together. It was braided between the past and present and held fast, a garrote that they used now as they had always used it. How nothing at all was long ago.

And there he spied, otherwise unrecognized but yet beloved, the devil still dancing to the music of the denial of that starlit past. He still had them, they still loved him, he truly did never die.9

“Taylor Mac’s 24 Decade History Of Popular Music”

Last week, “Taylor Mac’s 24 Decade History Of Popular Music” debuted on Max.10 On June 20, I was fortunate to welcome Taylor and the amazing team from the film to our cinema The Clairidge for a special preview screening11 and it was a deeply moving night. I’ve been fan of Taylor’s for several years— I was lucky to have seen one of the 3-decade, 3 hour performances (1956-66, 1966-76, and 1976-86) at St. Ann's Warehouse in the run up to Taylor's 24 Hour performance there. I was also proud to welcome Taylor to the Montclair Film Festival for one of the best events we’ve ever produced, a transformative, unforgettable performance that had a deep impact on everyone who attended. Despite my love of Taylor’s work, I didn’t make it to the full 24 hour show, and that remains one of my life’s great regrets.

One of the things that can only be understood and experienced when you address the fullness of the entire 24 decades is the deep connection the story of these songs have with one another, though time, in shaping a devastating portrait of how America and its culture continue to be formed. As the show pulls closer to contemporary time (from its origins in 1776), the more personal and emotional it becomes. History moves forward through time to become lived experience, and as it does, Taylor’s performance becomes more intimate, until, at last, it becomes what it has always been about: centering the recent trauma and negligent brutality of the AIDS epidemic and its devastating impact on the gay community as a crucial part of America’s historical continuum. But in that pain, a true cathartic grace is achieved— the artist and audience, having traced the history of music as both a tool of oppression and liberation, stand alone, together, united in song, holding one another up as a new day arrives.

We are so lucky to have this film as a document-- it absolutely delivers on Taylor's vision and had me in literal tears to finally see the full arc of this epic performance.12 But it arrives at a disgraceful moment in our shared history, as the LGBTQIA+ community, and the Trans community specifically, faces yet another wave of cynical bigotry, state oppression, discrimination, lies, and violence. If ever a moment required us all to stand together in support of our principles, it is right now. “Taylor Mac’s 24 Decade History Of Popular Music” is not only a vital historical proof for a society driven by its own deep desire for absolution in an ahistorical future, it also forges a path forward by reminding us that the only possible way for America to live her ideals is through an honest, conscious, and collective reckoning with the past.

Outro

If only every holiday had a song this good…

Thank you, family!

If only he knew what was to come…

I always thought Athens, GA was the “Athens Of The South”, but what do I know?

Uh, those confederate flags, so common back then, really stand out now.

Inspired by Charlie Pride?

Inspired by Tammy Wynette?

Inspired by Loretta Lynn?

Inspired by George Jones?

I had no idea I would finish this book on July 3, but holy moly… My first time reading this novel and it was incredible.

HBO 4 Ever!

Thank you so much to Taylor, directors Rob Epstein & Jeffrey Freidman, the amazing wardrobe genius Machine Dazzle, Producers Linda Brumbach, Alisa E. Regas, and Joel Stillerman for joining us for this special screening!

As someone who loves performance films, this one is an absolute must-see. Get to yer TV, turn up the volume, and do not miss it!! The perfect movie to celebrate the value of one another in our collective freedom.