As our culture continues its slow, aching bend toward acquiescence and accommodation of authoritarian power, ideas, principles, and propaganda, I am writing a series about the lessons of representation of authoritarianism and resistance in cinema. Thanks for reading and please share if you are so inclined.

Previously:

#1: SALÓ, OR THE 120 DAYS OF SODOM

****

On September 11, 1973, in Santiago, Chile, the democratically elected government of Salvador Allende was overthrown in a coup d’éat. As the Presidential palace was attacked, escape became impossible, and Allende took his own life1 rather than die at the hands of the fascist forces who had come to depose him. After Allende’s death, military Commander-In-Chief Augusto Pinochet was installed as President, leading the government junta of Chile for the next 17 years. In 1990, after a national referendum that demanded a return to democracy2, Pinochet handed the Presidency off to Patricio Alwyn, who was legally bound to keep Pinochet in the position of Commander-In-Chief of the military, where he stayed until 1998, when he transitioned to the role of “senator-for-life,” before being given a new position as “ex-president,” which granted him legal immunity and financial support from the state. Despite the work of domestic and international prosecutors to bring charges against him for human rights violations, when the time came to hold him to account, he was a frail, old man— finally placed under house arrest, he died of heart failure in 2006 at the age of 91.

The 1973 coup that deposed Allende is the subject of not only voluminous scholarship, but also one of the great documentary films of the 20th century, Patricio Guzmán’s extraordinary THE BATTLE OF CHILE, which delivers a blow by blow account of the fall of Allende’s government. Guzmán’s non-fiction work, which also includes 1997’s CHILE, OBSTINATE MEMORY (movingly detailing the erasure of the reality of the coup among young Chileans and the memories of older Chilean leftists who experienced life under the junta) and 2010’s NOSTALGIA FOR THE LIGHT3 (using Chile’s Atacama Desert as a symbol of both human possibility and the disappearance of thousands of political prisoners4), remains the definitive cinematic account of Pinochet’s coup and governance, shining a light on the junta’s brutal campaign against the tens of thousands of leftist political opponents who were murdered and/or tortured by the regime. But what of the realities of day to day of life under the fascist regime? What of the humiliations, moral compromises, and personal degradations that took place under Pinochet’s authoritarian control?

TONY MANERO is the Chilean director Pablo Larraín’s second feature film and the first in a series of works that explore life under Pinochet’s junta. Premiering at Cannes in 2008, just two years after Pinochet’s death, the film uses fiction and parasocial cinematic obsession to explore the ways in which the dictatorship created a permission structure for individual corruption to destroy the fabric of personal and social relationships. Among the many films that have sought to understand the individual under fascist rule5, TONY MANERO is, for me, the greatest cinematic example of the selfish heart of apolitical life, of how an indifference to politics can create the necessary space for atrocity, and how that indifference is not just a form of passive complicity but, as long as the individual allows himself to be aligned with and manipulate the pretexts of fascist rule, a form of active and deeply personal violence.

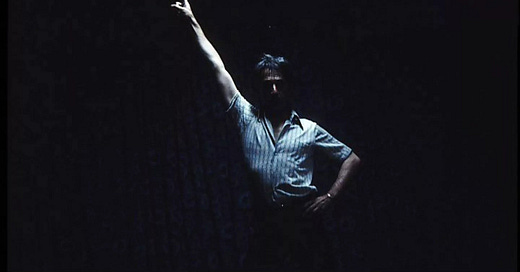

It is 19786 and Raúl Peralta (played by the incredible Alfredo Castro7) is a quiet man, living in a boarding house on the margins of life in Santiago. Raúl is singularly obsessed with John Badham’s 1977 film SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER and, in particular, the character of Tony Manero, played by John Travolta. The film has been screening for months in a run-down local cinema and Raúl has seen it innumerable times, studying Travolta’s performance and projecting a fantasy version of himself onto the character with an onanistic sense of awe. On the weekends, Raúl inhabits his dream self, leading a group of dancers who perform the routines from the film at a small dive bar. When a local TV show, dedicated to everyday people competing to see who does the best celebrity impersonation, decides to feature a contest for Tony Manero impersonators, Raúl’s deeply personal connection with the film inspires him to participate in the contest.

Raúl’s narcissistic, psychosexual identification with the details of Travolta’s performance sends him on a quest to find what he needs to succeed, undertaking a series of brutal murders and robberies to acquire the trappings of his fantasy life— a television, glass bricks that can simulate the famous illuminated dance floor from SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER, and more. When his castmates, who have been secretly participating in acts of political resistance, decide to compete in the contest too, he will stop at nothing to ensure they won’t make it to the show. Finally alone, he arrives at the TV studio to find multiple Tony Manero impersonators against whom he must compete. It does not go well.

Raúl’s psychopathy is a perfect vehicle for Larraín to explore the narcissistic indifference at the heart of apolitical complicity. When the specifics of the political violence at the heart of Pinochet’s regime do appear, they become signals for personal exploitation and opportunity8, a chance for Raúl to accomplish his goals. But he’s already laid the groundwork— his murderous rampage, driven by his escapist, delusional identification with Travolta’s Tony Manero9, is already a “doubling” of state violence, acts of brutality which, like his attempted “doubling” of Travolta, allow him to escape moral consequence and exert his pathetic, individual madness, disregarding the humanity of others in favor of expressions of “power” in pursuit of his delusions.

It is the intimacy of Raúl’s obsession, and his ability to use violence as a vehicle for personal transformation, that blinds him to the reality of the film’s shocking conclusion— he is not alone, there is an entire society willing to participate in this escapist fantasy, and while he is willing to sacrifice anyone and everyone to fulfill his dream of “becoming” Tony Manero, ultimately, he has misunderstood his own circumstance; authoritarian rule is completely indifferent to him, to his desires, his dream, regardless of the depths he is willing to plumb to fulfill his private fantasies. His apolitical position, created through murderous violence, is “doubled” by the authoritarian disregard for the individual.

Everything, it turns out, is for nothing.

And it is here, in the film’s final moments, that Larraín lands the decisive blow against the Pinochet regime— as meaningless as Raúl’s psychopathic individualism is, so too the state’s own murderous repression proves itself empty in the end. All of the torture, the murder, done in the name of preserving the power of a despot, and for what? The void of meaning is not a reflection of the politics, passions, and lives of the victims of state violence, those who gave everything to resist it, but rather, the emptiness of the state itself—unfettered by conscience, willing to do anything to serve the worthless, arbitrary demands of self-perpetuating power— corrupt, murderous, psychopathic.

Anyone alert to these conditions knows the echo now, can understand that the active violence of indifference has gathered force and is in plain sight— the mass disconnect from politics, legitimate threats passed off as “trolling”, or “jokes”, all of it seeking to test the conditions that will continue the normalization of expanding extrajudicial violence, where individual fantasies of the self as the sole subject of reality10 align with the delusional hypocrisy of an authoritarian system that uses people11 solely for its own ends.

We are experiencing something new to us— an emergent, seething, and brutal meaninglessness, dragging us toward empty fantasies of unaccountable personal power—

But, alas, it is not new at all.

For many years, Allende’s death was the subject of intense controversy, which seems to have been resolved in recent years. Read more about it here.

Among many others. His work is must-see cinema.

Pincohet’s regime “disappeared” people by using a favored technique— taking them up in helicopters and pushing them to their deaths, be it in the ocean or in the most remote areas of the Atacama.

We’ll be getting to those, I promise…

***SPOILER ALERT*** Although the date is never stated, the fact that GREASE arrives to replace SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER in the cinema, much to Raúl’s displeasure, implicitly tells us we are likely in 1978.

An incredible actor. This is the first role in which I saw him and he has become one of the few actors whose appearance in a film all but guarantees my viewership.

Raúl’s betrayal is not, of course, an “apolitical” act but his motivation is— a narcissistic psychopath, he sees every relationship as a form of selfish opportunity.

I just have to genuflect for a second: SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER, which details Tony’s attempts to escape the economic conditions of life in working-class Brooklyn by becoming an icon at the discotheque, is such a perfect choice for Raúl’s escapist obsession that I can’t believe TONY MANERO exists at all. For me? An incredible act of imagination, to find a fascist nightmare within a socially transformative blockbuster.

This is best expressed by the current video game derived labeling of people as “NPC”s, non-player characters, unconscious “objects” in that inhabit the world of the subject, the player, the hero of the game and, in this metaphor, “reality”.

Not me… “other” people. Until…

Great essay! Not familiar with this filmmaker, but going to check out Tony Manero tonight. Found it on Kanopy of all places.