The 2023 Cannes Film Festival opens tomorrow1 and I am here for it.

And by here, I mean home.2

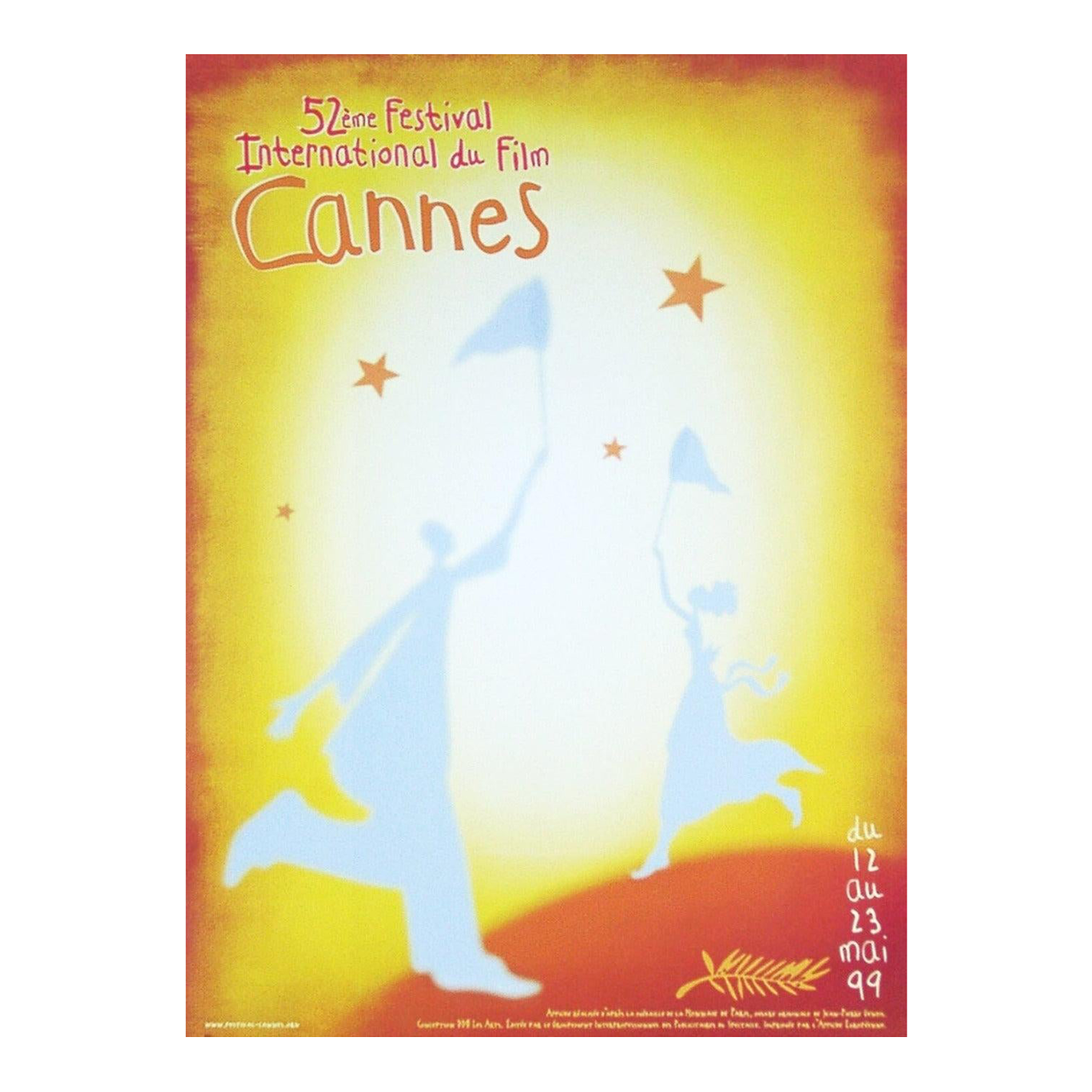

I have been to Cannes only three times in my career. My first trip, in 1999, was one of the defining experiences of my lifetime. As a kid from a working class city like Flint, MI, someone who raised himself on home video before landing in a college town just in time for the explosion of American independent film in the early 1990’s, I saw Cannes as an impossibility, a place that existed beyond my reach. That was, and for most people is, reality; say whatever you want about the festival, but accessible to the general public it is not.

That is also a choice. Cannes is explicitly designed for members of the film industry, and even then— a somewhat opaque, tiered badge system for press, a challenging ticketing process for industry attendees, a limited number of films screening each day, and an eye-wateringly selective main competition where films compete against one another for the festival’s awards— it is not exactly an open door. I know people hate it when I say it, because it sounds ridiculous, but Cannes is work. It is also my favorite place in the world to see a film.

The festival’s main screening rooms are housed in the Palais des Festivals, but ask anyone who loves movies— well, anyone who loves a certain idea of what the movies are— and they will likely agree that the Palais is less a “palace” and something more akin to a temple for true believers, a place for cinephiles to congregate and engage in a complicated relationship with not only contemporary cinema, but with the history of film. When you take a seat in the festival’s premiere screening room The Lumiére, having followed all of the historical protocols and current processes for accessing the screening, it is impossible not to feel like you are at the literal center of the global cinematic universe and that, for the next few hours, for you as it was for everyone who sat there before you, nowhere else matters at all.

When I made my first trip in 1999 for work, I got in the press line for an early AM screening, jet lagged and bleary-eyed, grabbed a seat in the balcony, and settled in for my first film, Bruno Dumont’s “L’Humanité”, which features an absolutely unforgettable opening sequence that, all of these years later, I refuse to spoil, but which let me know this festival was not going to be like anything else I had ever experienced.3 In that quiet, haunting moment, I was pried open by a sequence that had me reeling, setting the bar for what was ahead.

That year, I was able to see an unfathomably great lineup of films— “Ghost Dog: The Way Of The Samurai”, “All About My Mother”, “Pola X”, “Time Regained”, “The Limey”, “Ratcatcher”, “The Straight Story”, and unforgettably, “Rosetta”, which won that year’s Palme D’Or. Day after day, movie after movie, all of them unseen and brand new, it was overwhelming, incredible. I didn’t know if I’d ever get to go again4, but I was there, I made it, and it was a dream come true.

Sure, I felt a little like an imposter outside of the cinemas, but in the dark, watching? Everything changed. Even if, in the grand scheme of the festival, I was nothing more than another tuxedoed set of eyes occupying a seat, all of the barriers and protocols meant absolutely nothing once the films began— challenging, artful, completely indifferent to commercial prospects and filmmaking trends. I knew that Cannes was meant for someone like me. On the outside, it may seem like a true paradox that Cannes creates all of this pageantry— the red carpeted steps, the formal wear and fashion, hundreds of camera bulbs exploding, crowds of onlookers— only to then show some of the most challenging, modern, and rigorous films of the year, but that is Cannes. Experiencing these films in that context for the first time? If you are concerned about film as an art form, it is an absolute gift to see these specific films venerated in this way. It’s because of this that Cannes actually works.

No film festival embodies our collective, global cinematic history quite like Cannes, which has shaped the international conversation around filmmakers and filmmaking for decades. In a recent post about the contemporary state of film festivals and how they exist within the public’s imagination, I wrote about how, historically, Cannes built its position in the world of cinema by creating a “consensus of value and meaning” within the film industry. It bears repeating:

For the most part, because of its history and tradition, (Cannes) has its pick of World Premieres by directors from around the world who, by being programmed by the festival, immediately join the global conversation as artists that matter now. World Premieres are crucial to critics and to film media, because they provide the attending press the opportunity to be among the first to consider the work and contribute to the narrative that is built around a film, which is key to framing how films arrive in the world. That narrative helps drive and is coupled with the acquisitions and distribution market for each film, whose rights are bought and sold across global territories, with industry buyers and their teams coming to screen films (or, if they already hold the rights, to launch them), announce deals, and compete with one another to add titles to their distribution slates.

Film programmers, curators, and exhibitors also understand that premieres allow them to see and make decisions about which films might be a fit for their screens, positioning themselves to enhance their own place in the market by sustaining the theatrical life of a film in cinemas and at festivals around the world. All of these professionals come together at Cannes to play their role in developing a global path to reach audiences, make money, and compete for awards and prestige, for each and every film, each and every year.

In other words, Cannes has built an industry consensus of value and meaning for itself and, by association, for the filmmakers, companies, media, and professionals upon whom that consensus rests. And that consensus gives Cannes power. It gives Cannes the power to maintain its process, its values, its pomp, its curatorial exclusivity, and its global reach.

From its elevation of the art of film as a black-tie event to its enduring support of a long list of boundary-pushing filmmakers from around the world, Cannes is a festival that not only has the power to enshrine an artist in the history of film, but one that is fully aware of that power. This brings with it the ability to program almost anything the festival wants, and when you can do whatever you want, that absolute freedom comes with its own problems— Because Cannes chooses to be incredibly selective and loyal to its past, inclusion becomes a completely different challenge. Especially when inclusion as it is commonly understood today has never been a value at Cannes, which has literally defined itself by its exclusivity.

The festival was born in a different social, economic, and historical moment, but so was almost every other institution of power, and so, as it continues to see its curation as a part of a continuum, Cannes must navigate how to contextualize its relationship to the past in a contemporary moment of seismic change in the film industry, be it access for people who have been excluded from the production and celebration of cinema for far too long, or the new battlefronts that are reshaping the future of theatrical moviegoing. Cannes is more a declaration than a conversation— it is not a festival about democratic social participation in the movies. And yet, because of its power, Cannes has the power of choice, which is why there is valid frustration that the festival has not chosen to make inclusivity a priority for itself on a level that feels on par with the rest of the industry, especially at a time when elevating artists can be of such value artistically, and thus, socially and politically.

We live in a moment when films and theatrical moviegoing need more champions than ever, and so, while the festival must continually navigate a path to connect its ever-shifting present to its past, it is also hard to attend Cannes as a true believer in cinema and not be moved by being there. As a curator, I remain in awe of the films, the pomp, and the enduring power of Cannes as both an institution and an experience. As a person who can still access his own complicated feelings about the festival— the feeling of awe in attending, of dressing in black tie to attend a premiere, of marveling at the films themselves in those amazing cinemas, but also the feeling of impossibility, of watching from afar, of not being there, of Cannes not being for me, of being an outsider—I continue to hold both positions inside me at once. I remain both of those people.

So, I won’t be in Cannes this year, but as always, I am paying attention, following along on the festival’s YouTube channel, keeping track of the race for the world’s most coveted piece of arbitrary hardware (aka The Palme D’Or5), reading reviews in all of the trades, scouring social media for reactions to #Cannes, and doing my best to keep my envy in check until I can once again get back there to play my insignificant part in it all.

If you're going, never take it for granted. If you're not, you're not alone. Together, let’s see what this year holds because, no matter what, the cinema belongs to us.

This year’s Cannes Film Festival runs May 16th-27th, 2023.

I have too much to do! Again! Argh! I’ll be back soon enough.

Go watch it and then just imagine…

I did, in 2000 and then, after two decades of work, again in 2021.

Nine people vote and then give out the awards. As prestigious as the award is, it is the result of an agreement between nine people. Not the same nine each year, which might lend some insight into the process, but nine different people each year. No idea what their criteria are, how the decision is reached, etc. In this way, the Palme D’Or is the perfect award for Cannes.