In Part I of this series, we looked at landscape of the major Western film festivals through the lens of Cannes as a way to examine how a festival’s stature is built by creating consensus within the film industry around the commercial and artistic value in participation in and attendance at the festival. This consensus drives public perception through media coverage and acquisitions deals, film launches and reviews, red carpets and celebrity attendance, which in turn shape the public imagination about what a film festival can and should be. This creates a self-perpetuating gravity that allows Cannes to maintain its position as the premiere global film festival.

In Part II, we’ll take a look at what that means for the rest of us.

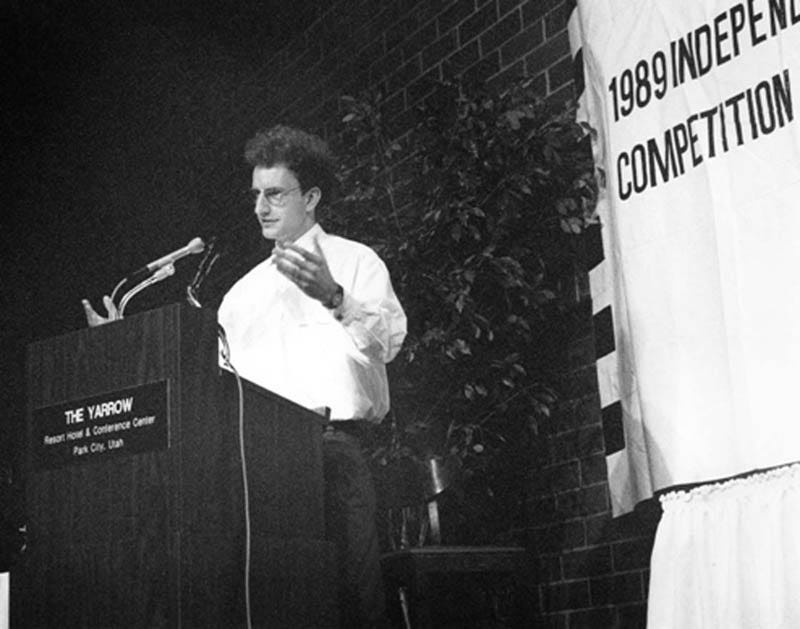

In 1989, an unknown filmmaker named Steven Soderbergh brought his debut feature film “sex, lies, and videotape” to the Sundance Film Festival, won the Audience Award, saw the film acquired by Miramax1 a couple of months later2, and changed the American film festival landscape forever3. From that moment forward, Sundance, situated in the picturesque ski resort town of Park City, UT, began a decades-long commercial revolution for independent American filmmakers by fostering an acquisitions environment for smaller, lower budget films. Sundance became the leading festival for World Premiering4 and selling an independent film and launching a career. The talent, film movements, and films that followed are, in essence, the recent history of independent film in America5.

Sundance has also had a less-discussed, secondary impact on film culture in America. Community leaders across the nation, seeing Sundance’s hip, celebrity-driven impact on Park City, decided that their own hometown6 could also benefit from the launch of a local film festival. And so, in the wake of Sundance’s ascending position in the industry landscape, America saw a surge in new film festivals in cities, towns, and communities across the country, each with its own mission and purpose, and exactly none of Sundance’s consensus of value and meaning for acquisitions, the industry, filmmakers, and press.

This massive expansion in American film festivals would have a two-fold impact on the industry; it created a viable (if patchwork) strategic path for filmmakers and companies to expand “word of mouth” and marketing reach for their films to new audiences at minimal expense7, and, simultaneously, established a secondary, relative value among film festivals who worked to create and distinguish their events within an emerging landscape of festivals of all shapes, sizes, and foci.

As new festivals began to position themselves on the calendar, the industry immediately realized that there was no way they could participate in each and every festival and, crucially, that the things that had created a consensus of value at Sundance were not viable at most other events— national and international press attendance was scarce, World Premieres were rare at best8, acquisitions even more so. And so, festivals began to develop other ways to establish their relative value to the industry— awards & Tributes, competitions & prizes, local and regional PR, exclusive locations & expensive parties, access to local money and film funding, and large audiences— which came to define what made various regional film festivals successful.

Of course, no single regional festival was doing everything well, but the smart ones tried to build upon their relative strengths, working toward what they could accomplish with limited budgets and staffing. While the scale was smaller, successful regional festivals did their best to “eventize” their festivals in ways that were meaningful9, not only to local audiences, but to a smaller constituency of the industry, who assessed festival opportunities on a relative (case by case) basis and began developing meaningful festival strategies for their films and talent.

This process, which is ongoing, has an impact not only on a festival’s position in the industry, but in a profound way, on programming and curation in particular. While industry consensus around the value of World Premieres allows festivals like Cannes and Sundance the opportunity to negotiate from a position of power when assembling their film lineups, the power dynamic radically shifts at smaller events; the curation process is not just a matter of “selecting” films, but of negotiating for them, of pitching the relative value of the inviting festival to the rights holder, of privileging and prioritizing companies and filmmakers with coveted films within the festival program, of leveraging a festival’s strengths to attract films and talent that will not only find an audience, but help the festival grow in prestige and establish as much relative value as possible, year after year.

While we talk about Cannes and Sundance as top tier festivals that have built a consensus of meaning and value, at most American film festivals, the process of curation is, essentially, a process of negotiation from a position of relative value.10 Of course, the narrative is different among media (who cover programming and curation as unilateral acts of decision making instead of collaborations among festivals, filmmakers, and rights holders) and audiences and the general public, who don’t really think too much about this stuff and who have internalized the narrative of “curatorial vision.” And in some ways, of course that is partially true: curators and programmers make choices, they decide which films they end up showing and, equally as important, which ones they don’t, what types of films speak to their festival’s identity, and in the end, the program gets discussed and evaluated by what ends up on the festival’s screens.

Today, in the wake of the ongoing challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic and the rise of streaming services moving the center of industry gravity and conversation to at-home viewing, festivals have continued to evolve into something else— a space in-between theatrical distribution and streaming, a space where, often11, streaming projects are welcomed into cinemas and in front of in-person audiences, lending the power of the collective cinematic experience to the work of artists and companies who still value it despite a distribution model that may not include theatrical exhibition. Festivals who were initially more welcoming to “day-and-date” strategies in the past seem to have established goodwill with industry partners who continue to experiment with theatrical windows, but for the most part, festivals have been on the same front lines of shifting theatrical moviegoing habits as film exhibitors, yet typically without the corporate dollars behind them to help sustain themselves in the face of declining attendance and rising costs. When they run out of money, however, non-profit film festivals don’t declare bankruptcy and consolidate their real estate portfolios. They disappear.

Yet even in the face of all of these changes, the dream endures. Sundance continues to received thousands upon thousands of submissions each year, primarily from emerging filmmakers who have seen so many influential careers and films launched at the festival. But Sundance is not immune to change; with an increasing number of distributors, streamers, and studios preferring the control of developing, producing, and distributing content in house, the festival acquisitions environment seems to be undergoing a real contraction.12 In parallel, while low and mid-size budgeted films and their attendant talent have migrated to this in-house production model, Sundance remains a preferred launching pad for these same films, while the festival's program remains roughly the same size. Which means that, for a filmmaker sending in an unsolicited film to Sundance, you're now competing with a greater number of distribtor-developed and agency-packaged projects. And so, the chance of submitting and being accepted into Sundance is, uh, not great.13

When the dream of Sundance and its surrounding narrative crashes against an infinitesimal acceptance rate, an annual tsunami of independent and emerging filmmakers find themselves operating outside of the distribution and acquisitions framework. This means that an enormous group of filmmakers, who saw the same career-making Sundance premieres and the same post-Sundance festival boom that everyone else saw, are forced to adjust their strategies and find another path to reach audiences. Even as things change, that path depends more and more on regional film festivals, the narrative of curatorial “choice,” and, unfortunately, a deep misunderstanding about the state of the industry.

In Part III of this series, we’ll look at how festivals and the film industry can work together to build a new path toward mutually beneficial ideas that enhance relative value and can help build new opportunities while deepening the culture of filmgoing in a sustainable way.

Yes, that Miramax. See Footnote 5 below.

Then went to Cannes and won the Palme D’Or, but I digress…

A gross oversimplification? Sure, but we have lots to talk about here.

Which served the same invaluable role for independent films that a Cannes World Premiere served for international auteur driven films.

Peter Biskind’s Down And Dirty Pictures tells this story far better and in much greater detail than I can here, and the book is a must for anyone interested in the history of American film festivals.

Or preferred vacation community.

I’ll put aside the depressing universe of “film festival scams” for the sake of time.

There are only so many high-quality films made each year, only so many distribution deals possible, only so many festivals with the financial infrastructure available to support the acquisitions and press required for a World Premiere driven program. In other words, there is only so much oxygen and almost all of it is already taken.

Often meaning, emulating the tropes of elite festivals like Sundance and Cannes — red carpets (with minimal press attendance but often featuring well-dressed locals), lavish parties paid for by the festival (vs private events funded by the industry), celebrity attendance (on a much smaller scale), director Q&As (in lieu of press conferences ala Cannes and or multiple media suites ala Sundance), etc etc.

There are some very interesting and important exceptions: SXSW— which built a for-profit film festival that leveraged the power of its brand within the music community to establish its own unique identity and develop a strong acquisitions & launch environment in the industry— and Telluride— which has been built upon a historical curatorial position of having leadership with such deep ties to industry stakeholders that it was able to shape itself into a powerhouse through a unique blend of equality of access among elite audiences and a consensus of value among important talent and decision makers— are the first examples that come to mind.

Cannes holding the line on streaming-only (no theatrical window) projects not playing the festival is yet another expression of the festival’s power.

Everywhere. Not just Sundance. Everywhere. And especially for non-fiction films.

Somewhere between .5% and 1.5% it seems.